Kashmir Tensions, Global Warming Put Indus Waters Treaty On Life Support

Today, more than 300 million people rely on the Indus River Basin for their survival

Kashmir Tensions, Global Warming Put Indus Waters Treaty On Life Support

In 1995, the then World Bank Vice-President Ismail Serageldin warned that whereas the conflicts of the previous 100 years had been over oil, “the wars of the next century will be fought over water.”

Thirty years on, that prediction is being tested in one of the world’s most volatile regions: Kashmir.

On April 24, 2025, the government of India announced that it would downgrade diplomatic ties with its neighbour Pakistan over an attack by militants in Kashmir that killed 26 tourists. As part of that cooling of relations, India said it would immediately suspend the Indus Waters Treaty – a decades-old agreement that allowed both countries to share water use from the rivers that flow from India into Pakistan. Pakistan has promised reciprocal moves and warned that any disruption to its water supply would be considered “an act of war.”

The current flare up escalated quickly, but has a long history. At the Indus Basin Water Project at the Ohio State University, we are engaged in a multiyear project investigating the trans-boundary water dispute between Pakistan and India.

I am currently in Pakistan conducting fieldwork in Kashmir and across the Indus Basin. Geopolitical tensions in the region, which have been worsened by the recent attack in Pahalgam, and the Indian-administered Kashmir, pose a major threat to the water treaty. So too does another factor that is helping escalate the tensions: climate change.

A fair solution to water disputes:

The Indus River has supported life for thousands of years since the Harappan civilization.

After the partition of India in 1947, control of the Indus River system became a major source of tension between the two nations that emerged from partition: India and Pakistan. Disputes arose almost immediately, particularly when India temporarily halted water flow to Pakistan in 1948, prompting fears over agricultural collapse. These early confrontations led to years of negotiations, culminating in the signing of the Indus Waters Treaty in 1960.

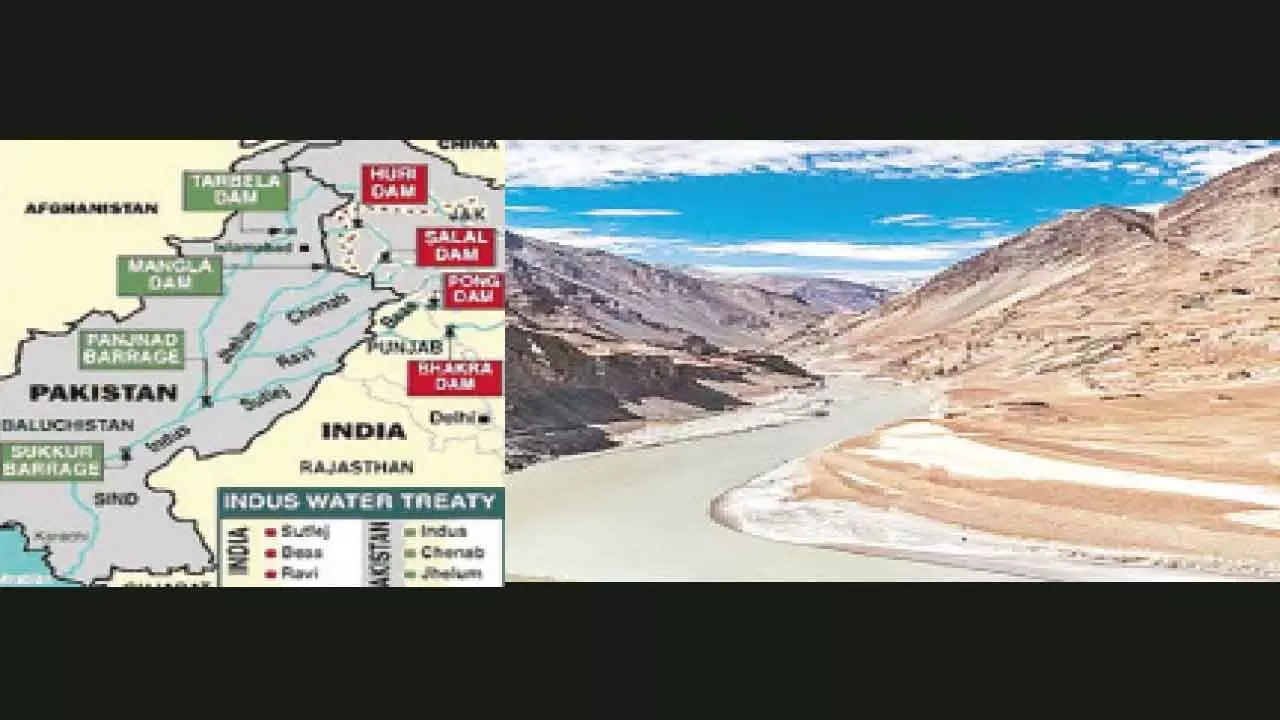

It divided the Indus Basin between the two countries, giving India control over the eastern rivers – Ravi, Beas and Sutlej – and Pakistan control over the western rivers: Indus, Jhelum and Chenab.

At the time, this was seen as a fair solution. But the treaty was designed for a very different world. When it was signed, Pakistan’s population was 46 million, and India’s was 436 million. Today, those numbers have surged to over 240 million and 1.4 billion, respectively. Today, more than 300 million people rely on the Indus River Basin for their survival.

This has put increased pressure on the precious source of water that sits between the two nuclear rivals. The effects of global warming and the continued fighting over the disputed region of Kashmir, has only added to those tensions.

Impact of melting glaciers:

At the time of signing, there was a lack of comprehensive studies on glacier mass balance. The assumption was that the Himalayan glaciers, which feed the Indus River system, were relatively stable.

This lack of detailed measurements meant that future changes due to climate variability and glacial melt were not factored into the treaty’s design, nor were factors such as groundwater depletion, water pollution from pesticides, fertilizer use and industrial waste. Similarly, the potential for large-scale hydraulic development of the region through dams, reservoirs, canals and hydroelectricity were largely ignored in the treaty. Reflecting contemporary assumptions about the stability of glaciers, the negotiators assumed that hydrological patterns would remain persistent with the historic flows.

Instead, the glaciers feeding the Indus Basin began to melt. In fact, they are now melting at record rates.

The World Meteorological Organization reported that 2023 was globally the driest year in over three decades.

The Himalayan glaciers, which supply 60-70 per cent of the Indus River’s summer flow, are shrinking rapidly. A 2019 study estimates that they are losing eight billion tons of ice annually.

A study by the International Center for Integrated Mountain Development found that Hindu Kush-Karakoram-Himalayan glaciers melted 65 per cent faster in 2011–2020 compared with the previous decade. Indeed, if this trend continues, water shortages will intensify, particularly for Pakistan, which depends heavily on the Indus during dry seasons.

Another failing of the Treaty is that it only addresses surface water distribution and does not include provisions for managing groundwater extraction, which has become a significant issue in both India and Pakistan. In the Punjab region – often referred to as the breadbasket of both nations – heavy reliance on groundwater is leading to overexploitation and depletion.

Groundwater now contributes a large portion – about 48 per cent – of water withdrawals in the Indus Basin, particularly during dry seasons. Yet there is no trans-boundary framework to oversee the shared management of this resource as reported by the World Bank.

A disputed region:

It wasn’t just climate change and groundwater that were ignored by the drafters of the Indus Waters Treaty. Indian and Pakistan negotiators also neglected the issue and status of Kashmir. It has been at the heart of India-Pakistan tensions since Partition in 1947. Despite being the primary source of water for the basin, Kashmiris have had no role in negotiations or decision-making under the treaty.

The region’s agricultural and hydropower potential has been limited due to restrictions on the use of its water resources, with only 19.8 per cent of hydropower potential utilized. This means that Kashmiris on both sides — despite living in a water-rich region — have been unable to fully benefit from the resources flowing through their land, as water infrastructure has primarily served downstream users and broader national interests rather than local development.

Some scholars argue that the treaty intentionally facilitated hydraulic development in Jammu and Kashmir, but not necessarily in ways that served local interests.

India’s hydropower projects in Kashmir — such as the Baglihar and Kishanganga dams — have been a major point of contention. Pakistan has repeatedly raised concerns that these projects could alter water flows, particularly during crucial agricultural seasons. However, the Indus Waters Treaty does not provide explicit mechanisms for resolving such regional disputes, leaving Kashmir’s hydrological and political concerns unaddressed.

Tensions over hydropower projects in Kashmir were bringing India and Pakistan toward diplomatic deadlock long before the recent attack.

The Kishanganga and Ratle dam disputes, now under arbitration in The Hague, exposed the treaty’s growing inability to manage trans-boundary water conflicts.

Then in September 2024, India formally called for a review of the Indus Waters Treaty, citing demographic shifts, energy needs and security concerns over Kashmir. The treaty now exists in a state of limbo. While it technically remains in force, India’s formal notice for review has introduced uncertainty, halting key cooperative mechanisms and casting doubt on the treaty’s long-term durability.

An equitable and sustainable treaty?

Moving forward, I argue, any reform or renegotiation of the Indus Waters Treaty will, if it is to have lasting success, need to acknowledge the hydrological significance of Kashmir while engaging voices from across the region.

Excluding Kashmir from future discussions – and neither India nor Pakistan has formally proposed including Kashmiri stakeholders – would only reinforce a long-standing pattern of marginalization, where decisions about its resources are made without considering the needs of its people.

As debates on “climate-proofing” the treaty continue, ensuring Kashmiri perspectives are included will be critical for building a more equitable and sustainable transboundary water framework.

Nicholas Breyfogle, Madhumita Dutta, Alexander Thompson, and Bryan G. Mark at the Indus Basin Water Project at the Ohio State University contributed to this article.

(The writer is Postdoctoral Scholar at the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center, The Ohio State University; Courtesy: https://theconversation.com/)